This year marks half a century since the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) transformed education in the United States. At its heart, IDEA is not just a law, but a statement of values about part of what it means to be human. Its very first words remind us:

“Disability is a natural part of the human experience and in no way diminishes the right of individuals to participate in or contribute to society. Improving educational results for children with disabilities is an essential element of our national policy of ensuring equality of opportunity … for individuals with disabilities.”

This landmark, human-centered, civil rights law established a vision of providing students with disabilities equal opportunity and full participation in our public education system.

In light of the 50th anniversary of the passing of IDEA, we want to celebrate the progress that has been made, while also recognizing that the vision has yet to be fully realized. Many of the educators teaching today were not born in the year or early years of IDEA’s passage, so let’s start with a brief overview of the impact IDEA has had on students with disabilities.

A lot has changed over the last 50 years. One thing that’s remained constant: education is human, relational, and communal work. People are the center of it all.

Before IDEA: A Different Reality

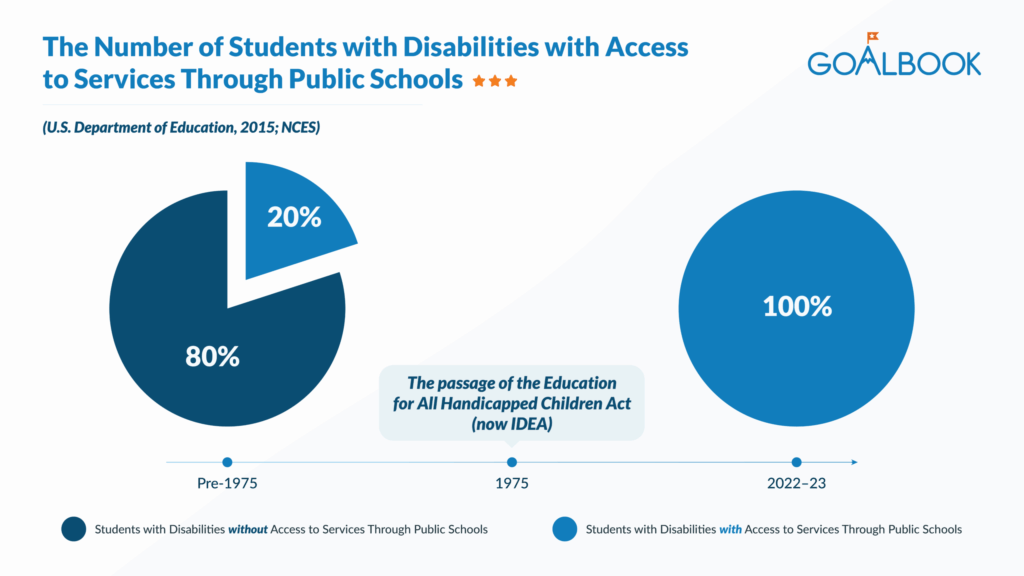

In 1975, The United States Congress found there were eight million children with disabilities whose special educational needs were not being met. One million of those children were excluded entirely from the public school system.

This means that only about 1 in 5 of those children with a disability actually received any education in public schools. And just 1 in 14 children overall were both identified as having a disability and served in school.

The rest—millions of children—were either excluded entirely from the public school system, placed in segregated classrooms that offered little instruction, or institutionalized without meaningful educational opportunities.

When data is presented, we can sometimes forget that the numbers represent actual human beings. They were someone’s son, daughter, grandchild, niece, nephew, cousin, friend. But because they had a disability, they were deemed unworthy of receiving a meaningful education.

Children with disabilities lacked access to an appropriate education, and schools faced little accountability. This was the reality IDEA was written to change.

The Passage and Intent of IDEA

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act was signed in 1975, and renamed in 1990 to the Individual with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

The purpose of the law is “to ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living.” (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.) Additionally, IDEA’s intent is to ensure the rights of children with disabilities and their parents are protected.

IDEA’s core principles can be viewed as commitments to the rights and humanity of children with disabilities and their families.

With these commitments, students with disabilities could, for the first time, enter classrooms alongside their peers, and begin to claim the education once denied to them.

50 Years of Milestones and Accomplishments

Before the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1975 (now IDEA), Congress estimated that about eight million children—roughly 16% of the school-aged population—had a disability. Yet only 1 in 5 of those children were actually served in public schools, leaving millions excluded or receiving little to no meaningful instruction. In practice, that translated to an estimated 3% of all K–12 students nationwide in 1975 that were provided special education services (U.S. Department of Education, 2015; NCES).

Today, the picture looks dramatically different. In the 2022–23 school year, about 7.5 million students ages 3–21 received special education services under IDEA, representing 15% of total public school enrollment (NCES, 2023). Whereas 1 in 5 students with disabilities were served in public schools in 1975, thanks to IDEA, today all students with disabilities and families have the right to access services through public schools.

Throughout the years, key amendments to the law have deepened protections and outcomes for students with disabilities. These include:

- 1990 Amendment: Renamed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act to Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Additionally, recognized Traumatic Brain Injury and Autism as covered disabilities.

- 1997 Amendment: Ensured students with disabilities were no longer seen as separate from the general school system and had to be included in the general education, assessed with their peers, and supported with structured IEPs. Families gained more voice, and schools gained clearer rules for behavior and discipline.

- 2004 Amendment: Shifted special education toward being more human and future-focused by holding schools accountable for real learning outcomes, expanding early support and streamlining IEPs so teachers and families can focus on the child—not just compliance. Emphasized high expectations, inclusion, and preparation for life beyond school.

Since 1975, students with disabilities have gained the right to be present, be supported, and be prepared for meaningful lives. Due to the collaborative efforts of families, schools, and IDEA, there have been gains for students with disabilities:

- Greater inclusion in general education settings. About 67% of students with disabilities spend 80% or more of their time in general education classes.

- Increase in graduation rates and postsecondary access. 74% of students with disabilities graduated with a high school diploma, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

All students benefit from inclusive classroom settings. For students with disabilities, these milestones mean they have more educational opportunities. Studies indicate that students in inclusive settings “engage in more rigorous courses of study and are more prepared for successful post-secondary educational and employment opportunities” (Morningstar, et al., 2022). For students without disabilities, evidence shows “peer acceptance and friendship rates are higher in inclusion classes than traditional general education classes, and students without disabilities have more favorable attitudes toward students with disabilities” (Kart & Kart, 2021).

While these milestones show the transformative power of IDEA, they also remind us of the work still ahead.

IDEA Challenges That Remain

Despite the accomplishments made throughout the years, there are still persistent challenges for students, educators, and funding in special education, as well as the fulfillment of IDEA.

For Students

Students with disabilities still face gaps in academic achievement. For example, in 2024, there was a 39-point achievement gap in reading assessment scores between students with disabilities and students without disabilities in 4th grade. For 12th-grade students, the gap in reading assessments was 38 points. (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], n.d.)

Children with disabilities are more likely to be disciplined, removed from classrooms, suspended, or expelled than their classmates without disabilities. The 2020-21 Civil Rights Data Collection reported that while students with disabilities served under IDEA represent 14% of total K–12 enrollment, they represent 32% of students mechanically restrained, 81% of students physically restrained, and 75% of students secluded.

For Educators

The shortage of special education teachers has existed almost since the inception of IDEA. Special education teachers leave at a higher rate than their general education peers.

Working conditions are a significant reason special educators attribute to leaving the field. The imbalance between educator responsibility and access to available resources leads to lower-quality instruction, stress, burnout, and ultimately, attrition (EdResearch for Action, 2022).

As a result of the shortage, many schools hire uncertified or emergency-credentialed teachers, despite the law requiring fully certified staff.

The complicated problem of staff shortages is exacerbated by the rising number of students being served under IDEA. To make matters worse, although there is an increased demand in special education services, the funding has stayed the same or decreased over the years.

In Funding

When IDEA was enacted in 1975, it was initially pledged that the federal government would fund 40% of the national per-student expenditure for special education services. However, the actual federal funding for special education has consistently fallen short of this commitment, currently providing less than 13%, with some estimates being closer to 10%.

The gap in federal funding creates financial strain and impacts the quality and extent of special education services provided to students with disabilities.

These challenges are not failures of IDEA’s vision—they are reminders that civil rights laws require vigilance and leadership to be realized.

Hope for the Future

IDEA is not static, nor is it antiquated. It is a living promise to students with disabilities that requires constant stewardship.

Educators are the primary stewards of that promise. Every day, they carry forward the vision of human dignity and opportunity for all students. Research consistently shows that educator effectiveness has the greatest impact on student achievement. That is why it is essential to honor and support the dedication of educators whose work keeps IDEA’s vision alive in classrooms across the country.

At Goalbook, we are committed to sharing in this stewardship. From the very beginning, our mission has been to empower educators to transform instruction so all students can succeed.

Education has always been human, relational, and communal work. People—educators, families, and students—are at the center. As we look to the next 50 years, our commitment is to continue partnering with educators to move the field of special education forward with impact, innovation, and above all, a shared dedication to students.

References

EdResearch for Action. (2022). Special education staffing: Effective strategies for addressing shortages (EdResearch for Recovery Design Principles Series, Brief No. 31). Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://edresearchforaction.org/wp-content/uploads/55015-EdResearch-Special-Education-Staffing-Brief-31-FINAL-1-1.pdf

Kart, A., & Kart, M. (2021). Academic and social effects of inclusion on students without disabilities: A review of the literature. Education Sciences, 11(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010016

Morningstar, M. E., Kurth, J. A., Carter, E. W., Erikson, K. A., Turnbull, H. R., Anderson, D., Clark, K., Eisenman, L. T., Newman, L., Plotner, A., Shaw, L., Shogren, K. A., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2022). Quality indicators for secondary transition services and practices. The Journal of Special Education, 56(4), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669221097945

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Achievement gaps dashboard. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/dashboards/achievement_gaps.aspx

U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, subchapter I—general provisions §1400. IDEA. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/statute-chapter-33/subchapter-i/1400U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights. (2023). Civil rights data collection: Data snapshot (College and career readiness).